A collision with a logging truck, on a sunny December day in 1999, broke Mindy Harris' collarbone, lower back and three vertebrae in her neck.

But the logging truck wasn't how Harris lost her leg. At least, not directly.

It was the flurry of prescription painkillers she got hooked on after the crash. It was the heroin she turned to after doctors cut her off. It was the heart lining, infected from a bad batch of heroin, that broke off and blocked blood to her left leg — sending her into a three-month-long coma and, eventually, under a doctor's knife to amputate the leg.

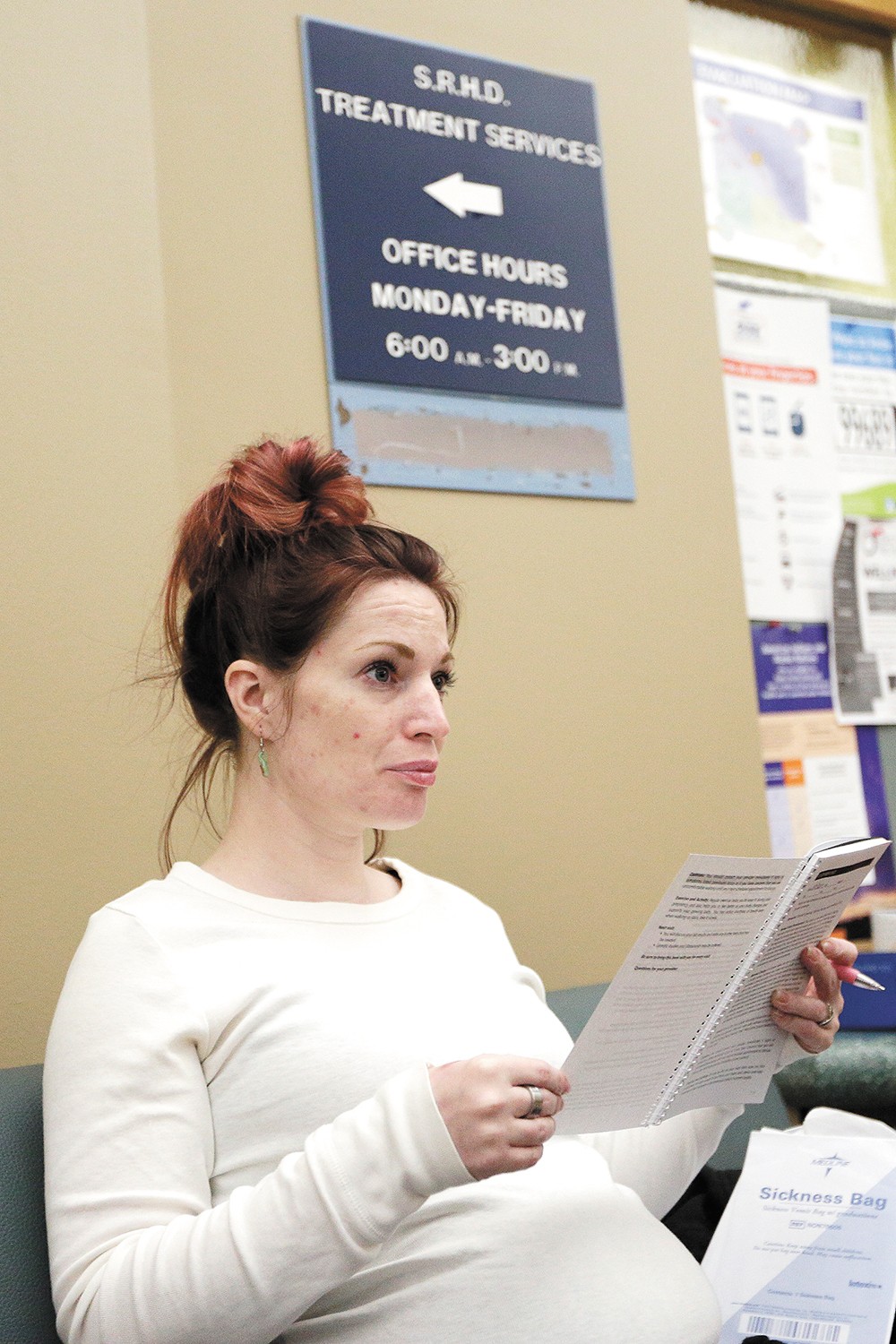

That is what has led her, now in a wheelchair, to the Spokane Regional Health District for a dose of legally prescribed methadone. But today, she's smiling broadly. She talks fast, with a frantic eagerness, a happiness even. She says there's hope.

She says she's been clean since April.

"I told my mom, the reason I've been clean so long was because I was on methadone," Harris says. "It's the best thing that has every happened to me. ... I look forward to tomorrow, instead of dreading it."

Harris already has seen too many friends and family members killed by drugs. Nationally, more people died of drug overdoses in 2016 than all the murders and fatal car accidents combined — even more than the number of Americans killed during the entire Vietnam War.

Most of those deaths are from opioids.

Last year, overdose deaths in Spokane County climbed to 111 — the most overdose deaths since 2008, according to the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. More than half were opioid-related. And the problem has been shifting from prescription drugs to heroin.

Across the country, the epidemic has forced a radical shift in drug rehabilitation — away from cold-turkey, abstinence-only rehab and toward swapping out deadly addictive drugs for safer alternatives.

So while the pharmaceutical industry has largely been blamed for fueling the opioid epidemic — marketing drugs like OxyContin as medical miracles while downplaying their risks for abuse — most experts now agree that pharmaceutical medications are the only proven way to combat the resulting addiction.

But trying to implement that solution isn't easy. There's the stigma of treating drug addiction with more drugs. Plus, an outdated bureaucracy and underfunded health system make it easy to prescribe painkillers — but hard to dispense drugs that could fight related abuse.

"It's just weird! What, we're worried about too much addiction treatment?" scoffs Keith Humphreys, a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University who worked with the Bush and Obama administrations on drug policies. "Why aren't we worried about the fact that we prescribe more opioids by a factor of six than all other developed countries?"

TREATMENT, NOT A CURE

The doors to Spokane's methadone clinic swing open at 8 am, and Harris and dozens of others flood in, each of them grabbing a red ticket.

When Harris' number is called, she wheels into a tiny room with a small window, where a nurse hands her a cup. Harris throws back her head and swigs it. The cherry flavoring can't hide the terrible taste, she says.

Harris gets counseling and group therapy here. But this red liquid, in a tiny clear cup, is what's made the difference.

Today, the Health District's methadone clinic has more than 960 clients, each with their own story of addiction. For Harris, it was her car accident. For Kirk Abbott, a white-bearded 68-year-old, it was the horror of the Vietnam War. For Victoria Justice, a copper-haired 28-year-old, it was the hydrocodone she was given during the birth of her first child, coupled with the pain of an abusive relationship.

Each of them is here to swap out a dangerous drug for a safer one. While methadone is addictive and potentially deadly, it doesn't produce the same rapid high as heroin. It lasts longer. Tightly regulated, it's much less risky.

As the battle against the opioid epidemic rages, researchers and medical experts have converged on "medically assisted treatment," using drugs like methadone and Suboxone, as the most effective way to treat opioid addiction and reduce the dangers of overdoses and relapses.

But many addicts aren't offered this kind of treatment — and some say they don't want it.

Matt Layton, former medical director of the opioid treatment program at the Spokane Regional Health District, says the stigma can scare them away.

"They have family members who are saying, 'You're just replacing one addiction with another,'" Layton says.

"I was so sick. When I got out of jail, I would have went right back to living in my car and using heroin. I know that for a fact." — Sabra Bouchillon, a methadone patient in Spokane

tweet this

In May, Tom Price, then the Health and Human Services Secretary, made a similar comment, to the medical profession's horror: "If we're just substituting one opioid for another, we're not moving the dial much," he said. (Price resigned under pressure in September after racking up at least $400,000 in travel bills for chartered flights.)

Price's statement flies in the face of President Donald Trump's own Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, which found that medication-assisted treatment was tied to "reduced overdose deaths, retention of persons in treatment, decreased heroin use, reduced relapse, and prevention of the spread of infectious disease."

Yet according to a report by the presidential commission, a full 85 percent of counties in the United States have no substance abuse treatment facilities with an opioid treatment program.

Some of that has to do with philosophy. Despite the growing medical consensus, many rehab facilities have been wary of using methadone or Suboxone.

Not only do many rehab centers refuse to prescribe opioid-replacement medication, they won't admit some patients because of it.

Julie Albright, the Spokane methadone clinic's treatment administrator, says that neither Union Gospel Mission's women's recovery program, nor Spokane Addiction Recovery Centers, accept patients from the Health District's methadone clinic.

In an email, Linda Kruger, programs coordinator for Spokane Addiction Recovery Centers, says the clinic will work with some patients on medications, but remains abstinence-only. Asked about the case for using pure abstinence instead of opioid-replacement medication, Kruger writes, "I would recommend attending any open 12-step meeting in our community."

To explain the skepticism many treatment centers have about medication-assisted therapy, Keith Humphreys, the Stanford professor who worked on federal drug policies, points to the history of the drug treatment system. It wasn't birthed from the world of medicine. It came from the criminal justice and social welfare systems, and from peer-self-help programs like Alcoholics Anonymous.

"It's got a long history of living in the shadows, being apart from medicine, not being well-covered, having a lot of underpaid staff," Humphreys says.

And while traditional rehab may work for some drugs, opioids are different. They're particularly difficult to kick and particularly dangerous when you do.

That's because for heavy users, opioids alter the chemistry of the brain. The drugs lock on to the same pleasure receptors as those endorphins released after rigorous exercise. But they're far stronger than natural chemicals, overstimulating these receptors. So the brain compensates. You start to need bigger and bigger doses to reach the same high. Your cravings increase, and you feel more and more miserable without the drugs. The withdrawals are excruciating.

"If you've ever had a boulder bounced off your head," Harris says, then you know what the withdrawal feels like. Every bone in your body, down to your littlest finger, is aching, she says.

"I was pooping my brains out," Harris says. "Throwing my brains up."

Harris remembers gritting out opioid withdrawal symptoms for 18 days when she was cut off. Then she turned to meth instead, and when that didn't work, bought opioid pills on the street.

"This is like the devil with your soul. Here's your soul in his hands," Harris says. "There's absolutely nothing you can do to get your soul back."

Nearly 90 percent of addicts relapse within nine months without medication, says Layton. And when they do, it can be deadly: They'll have lost tolerance to the drug — the same dose of heroin they were taking before quitting can be fatal when they start using again.

Still, it's true that medication-assisted treatment doesn't work for everybody. Critics also point to how rapidly most addicts return to using illicit drugs if they stop using methadone.

Indeed, the Spokane Regional Health District acknowledges that for many addicts, methadone will be a lifelong regimen. But Humphreys says opioid-replacement drugs are like birth control pills — they only protect you while you're taking them. He says we need to treat opioid addiction more like diabetes. Nobody shames patients for taking insulin for the rest of their lives.

For those at the methadone clinic, the drug has allowed them to climb out of homelessness, return to work or repair relationships.

"I don't get high. I'm not after that high. I'm not chasing that high," Abbott says. "I'm normal. Whatever normal is."

Funding challenges have also stopped patients from getting methadone treatment. A few years ago, the clinic was capped at 550 patients and had a three-year waiting list.

Since then, Layton says, the methadone clinic has expanded dramatically. Credit state money from Obamacare's Medicaid expansion.

Today, the clinic serves 950 patients and has whittled down the wait list to a month. But problems remain: Unlike Medicaid (for low-income people), Medicare (for those 65 and older) still won't pay for methadone administered in a opioid-treatment center — meaning that the county has to dip into grant funding to help elderly patients. It's a problem that Trump's opioid-crisis commission says needs to be fixed.

There are other problems. For years, the Health District would watch their methadone clinic patients get arrested, go to jail and lose access to their methadone. They'd go through withdrawals and often start using again after they were released.

In February, thanks in part to changes in Drug Enforcement Administration regulations, the clinic was able to expand to begin treating pregnant women and current methadone clinic patients at the Spokane County Jail.

Sabra Bouchillon, 31, cradles her newborn, Miles, in her arms. She was pregnant when she went to jail in February. Opioid withdrawals can kill an unborn child, depriving the fetus of oxygen and causing fetal seizures.

"I would have miscarried for sure," Bouchillon says. "I was so sick. When I got out of jail, I would have went right back to living in my car and using heroin. I know that for a fact."

Instead, she says, she got to hear her baby's heartbeat. It was the sound she clung to, a motivation that fuels her recovery.

Yet there are still prisoners who don't have access to methadone treatment, despite an opioid addiction. Inmates lose their Medicaid while they're incarcerated, forcing the county to find other sources of money for methadone treatment.

Starting next month, $183,000 of state Criminal Justice Treatment Account grant funding will help provide methadone treatment for additional jail inmates for nine months.

"But it's not a lot of money," says Albright, the Spokane methadone clinic's treatment administrator. When it runs out, they'll lose access again.

RED TAPE AND ORANGE PILLS

Unlike other medicine, many addicts needing methadone have to show up in person, six days a week, in order to get it. For Victoria Justice, who lives in Wellpinit, traveling to the clinic is like a full-time job. In the winter months, it means getting up before dawn and catching the 6:15 bus to make it to the clinic. The bus doesn't come back until noon. That's 36 hours over the course of six days a week. Still, she's grateful to be there.

"It gave me my life back, literally," she says.

For some patients, however, the time commitment can become a massive barrier, something that could stop them from sticking with treatment.

Only after months of successful visits without failing a drug test will state regulations allow methadone clinics to dispense additional "carries" — sealed bottles with multiple doses of methadone that patients can take home in a locked container.

There's value, of course, in rules, Layton says. The structure can help keep patients accountable and safe. But he also argues that doctors need the right to use their judgment to tailor their care to patients.

Earning the right to bring home two weeks worth of methadone can take two years, Layton says. Fail the wrong drug test, like testing positive for alcohol, and state regulations say that privilege can be lost in an instant.

Julie Albright has seen clinic patients drive hours from Moses Lake, Walla Walla or Montana, six days a week, to get methadone.

"Can you imagine, for your diabetes, if you had to drive daily to get your medication?" Albright says.

Rural communities, which have been hit hardest by the opioid epidemic, often don't have a methadone clinic nearby.

There aren't any methadone clinics at all in North Idaho, forcing addicts to come to Spokane, Albright says. But since they're enrolled in Idaho's Medicaid program, instead of Washington's, they're charged cash. That's $15.25 a day, more than $470 a month, over $5,500 a year.

"That's a really nice car payment," Albright says.

By contrast, it's not hard to find doctors in Idaho willing to prescribe methadone pills for pain instead of addiction treatment.

That's the really absurd thing, Layton notes. Most of these hurdles don't apply to doctors prescribing opiates — including methadone — for pain relief instead of addiction.

The good news is there's another opioid-replacement drug that isn't quite as strictly regulated: Suboxone, generically buprenorphine, comes in the form of little orange tablets that light up the same mental receptors that methadone or heroin does, but not as brightly.

It's not as dangerous or addictive as methadone — but it's also weaker. Taken alone, without other drugs, you can't overdose on Suboxone. For extremely heavy opioid users, it's often not powerful enough. Some sell their pills on the street when it doesn't work for them and use the money to buy heroin.

But Suboxone has the big advantage of being able to be prescribed by primary care doctors.

"That's appealing to a lot of patients who don't want the stigma of walking into a heroin clinic every day," Humphreys says.

Six years ago, Ideal Option, a clinic that prescribes Suboxone, opened in the Tri-Cities. Today, the company has expanded rapidly, with more than 20 clinics in Washington, Idaho, Montana, Alaska and Maryland.

"We used to have a 500-person waiting list in that area about a year ago," Jeff Allgaier, president of Ideal Option, says about the Spokane region. "We have made a priority of ours to not have a waiting list. These people need treatment right away, or they die."

Increasingly, Suboxone is being seen as a crucial tool in the fight against addiction. Sacred Heart Medical Center starts some addicts on it in the emergency room after overdoses.

"It's not abused in the traditional sense," says Darin Neven, a Sacred Heart emergency room doctor. "I think Suboxone should be a behind-the-counter medication you can get from a consultation with a pharmacist."

But it isn't.

Doctors who prescribe Suboxone still face significant regulations. Practitioners are required to get a DEA license, extra training and a specialized waiver to prescribe it. Up until this year, nurse practitioners couldn't prescribe Suboxone at all — only doctors could. And doctors still have a federal cap for how many patients they can have on Suboxone treatment — only 30 for the first year. Some insurance carriers don't cover taking Suboxone or methadone treatment at all.

Humphreys, for one, doesn't want Suboxone unregulated — he still believes it's important to provide counseling instead of just shelling out pills — but he believes the balance is out of whack.

It remains easier to prescribe more addictive opioids for pain, he says, than to prescribe Suboxone for addiction.

"If they want to just hand them a bottle of Oxy, that's fine," he says. "Those incentives are all screwed up."

DEADLY DELAYS

When an overdose patient comes into Sacred Heart's emergency room, Neven does what he can to save their life and get them stable. But some of them need more than that. Many of his patients don't just need to get connected with a Suboxone or methadone clinic, he says, they need to go to rehab.

They might need to go to a detox clinic, or get help for addictions to multiple drugs, and work on other issues in their life.

"A lot of the most severe addicts need inpatient treatment with medication-assisted therapy," Neven says. "There's a tremendous amount of red tape and hoops you have to jump through in order to get into treatment."

Those delays can be fatal.

Although there are a number of residential rehab facilities, medical detox facilities are rare in the region. Until American Behavioral Health Systems opened a new facility this fall, there wasn't an acute medical detox center that took Medicaid in all of Eastern Washington.

One major insurance carrier in Spokane won't pay for any inpatient treatment in the area, Neven says. There may be a weeks-long waiting list. Even if there is a bed available, it can take three to five days, minimum, to get approval, he says.

During that time, addicts often change their minds.

"That's what breaks my heart," Neven says. "I don't know where they're going to be at in 3 to 5 days."

Spokane Police Capt. Brad Arleth, a 25-year veteran of the department, says police officers know how crucial it is for addicts to get treatment immediately.

"With addiction, no matter what kind it is, when somebody says they need help and they're willing to go — " Arleth snaps his fingers. "They got to go now. Like, an hour from now."

Give addicts time to think about it, Arleth says, and their first stop isn't going to be rehab. It's going to be their drug dealer.

While Spokane's drug and community courts often send addicts to rehab, Arleth says that, unlike King County, Spokane doesn't have a program that allows cops to send offenders directly to treatment before they're charged.

But even for those who do get into inpatient rehab, relatively few opioid addicts will receive scientifically backed, medication-assisted treatment. Even at clinics that support opioid-replacement drugs, the use of these medications is limited.

At Sun Ray Court, a Spokane inpatient facility for up to 54 men, only about 10 to 25 percent of opioid addicts are receiving medication-assisted treatment.

"We don't have a Suboxone prescriber on staff," says administrator Tom Cook. "I don't have the funds to employ someone who would actually work here, who would have the credential."

And of the nearly 100 patients being treated for opioid addiction at American Behavioral Health Systems in Spokane, only about 30 percent are on a full opioid-replacement treatment regimen.

Paul Means, a nurse practitioner who works with ABHS, says the biggest issue is that, while he can start patients on Suboxone during their short stint in rehab, he needs to have a Suboxone provider he can hand them off to afterward. And they can be hard to find.

"The bottleneck in the whole system is the numbers of providers who can prescribe Suboxone," Means says. According to the opioid crisis commission's report, nearly half of the nation's counties last year didn't have a single provider with a waiver to prescribe Suboxone.

Sometimes, the patients are the ones who refuse Suboxone.

"Half of patients don't want to be on medication," Humphreys says. "You can't just tell them 'Go to hell.'"

But what Humphreys objects to are the drug courts and treatment centers, across the country, that refuse to even offer medication-assisted therapy. There are judges, he says, who say "no methadone in my courtroom," despite having little medical expertise.

At Spokane's Community Court, which often will refer addicts to treatment programs, coordinator Brianne Howe strikes a middle ground.

"I think the belief that all those addicted to opioids need medication-assisted therapy is misguided," Howe says by email. "Some can obtain and maintain complete abstinence, while others may need a short term or long term medication-assisted therapy."

But Allgaier, the president of Ideal Option, has a different objection. When traditional courts order drug treatment, they do so by requiring defendants to get a chemical dependency assessment to recommend the best treatment option. But Allgaier says the people who make these assessments have relatively little medical training.

"You get counselors that their main experience is that they're former addicts themselves," Allgaier says. And while some of them are great, he says that too many are hesitant to put patients on medication-assisted treatment.

"We've gone the chemical dependency professional route, for how many years? We've gone that route," Allgaier says. "And many people are dead because of it."

HARM REDUCTION

Some community leaders, like City Council President Ben Stuckart, have suggested the city needs to seriously look at a model in Vancouver, B.C. There, at "supervised injection sites," heroin users are allowed to shoot up — in full view of medical staff who try to prevent overdoses and connect the users with services.

"I think it's something we need to discuss," says Dr. Bob Lutz, health officer for the Spokane Regional Health District. "To run away from the issue of IV drug usage is to play the ostrich, to bury your head in the sand."

For 26 years, Spokane has had a needle exchange program, but this would be more radical and expensive, and far more controversial. While research suggests that the model reduces the rate of overdoses and HIV and Hepatitis C infections, the backlash can be considerable.

After a King County opioid task force recommended the creation of two injection sites on the westside, Washington state Sen. Mark Miloscia warned that they would "literally turn Seattle and King County into the heroin capital of America."

Such efforts can be expensive, Layton acknowledges, but he compares the stigma against it to the stigma against passing out condoms.

"If you're leaving bloody syringes in the playground? Would you rather someone go to a safe injection site than shoot up in the park and leave a needle?" Layton says. "I would say yeah."

But for many, any policy change or miracle medication is already too late.

That much is evident in the waiting room of the methadone clinic, where a wall is decorated for the Day of the Dead. Patients from the clinic and needle exchange have covered it with notes to friends and family members who've passed away.

Some are apologies: "I'm sorry my addiction led me to let you die of cancer all alone in that nursing home." "I'm sorry my addiction couldn't stop long enough to say goodbye at your funeral."

But most of the notes are written to loved ones who've been lost to overdoses. "You are my 'Little Sunshine.'" "Hey Sharky, miss swimming around in this bigass pond we call livin' life." "Stew — I really, really miss you. Rest with the Lord now."

Six years ago, Mindy Harris' younger stepbrother, Will, died of a heroin overdose. On Dec. 3 of last year, her older stepbrother, Donald, died of an overdose too. She says she misses his sense of humor, the way he laughs, his goofy Jim Carrey impressions.

"It opened my eyes: 'Oh my God, that could have been me,'" Harris says. "I wasn't clean for [nearly] 20 years... Since I've been clean, family means a lot."♦

A Way Out

This is the first in a series of stories examining drug addiction, its toll on our community and, importantly, how people are finding a way out. Send feedback and story ideas to [email protected].

ON THE CUTTING EDGE

Recently, several encouraging studies have looked into the effectiveness of a drug called Vivitrol (generically, naltrexone). Unlike methadone or Suboxone, it isn't an opioid. Instead, it works by blocking the receptors instead of lighting them up. But it can be injected in a form that lasts a full 30 days, both removing cravings and effectively making heroin inert. Users can take heroin, but it won't get them high.

For certain users, the drug can be incredibly effective. Already, the oral form is being used for patients at American Behavioral Health Systems residential clinics.

And more cutting-edge research is being conducted in Spokane. Matt Layton, former opioid program medical director, and a team of doctors and nurses from WSU's College of Medicine are running an experiment looking at a possible way to treat opioid addiction with oxygen. Studies have suggested that when flooded with oxygen, mice don't suffer such severe symptoms from withdrawals.

This week, they're testing it on humans: Volunteers from the methadone clinic will go inside a hyperbaric chamber that looks like a submarine, don a clear plastic oxygen hood, and then be flooded with pressurized oxygen for 90 minutes to see if it helps their withdrawal symptoms.

"We're looking for any answers to help us to get people off of opioids," Layton says.

— DANIEL WALTERS

PUTTING OUT FIRES

Last year, the Spokane Fire Department used Narcan on 145 occasions, attempting to save the lives of people who seemed to be experiencing a severe overdose. This year, with less than two months left, the number is even higher, at 175.

Narcan wakes addicts up from an overdose. They can start breathing again. But it also rips them back into reality. Some addicts get angry at the paramedics who just saved their life for taking away their high — they ask to be left alone and try to leave.

Doctors at Sacred Heart Medical Center's ER used to give Narcan to overdose victims to take home, training their loved ones on how to use Narcan to save their lives if they overdose again.

But in 2015, a state Pharmacy Quality Assurance Commission rule banned Washington state hospitals from giving patients prepackaged take-home medications. The legislature swiftly passed a bill to create an exception — but only for hospitals without access to 24-hour pharmacies.

— DANIEL WALTERS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Daniel Walters covers Spokane City Hall, business and development for the Inlander. Since 2008, Walters has detailed Spokane's ongoing fight to end homelessness, investigated the lack of mental health access across rural Idaho, exposed the flaws of the Washington state foster care system and dug into the causes of the region's sky-high property-crime rate. Reach him at [email protected] or 509-325-0634 ext. 263.